This is a follow-up of the article Underground psychoanalysis in Prague – part I.

Now, I would like to cover several themes which I consider to be most significant in the formation of Prague psychoanalysis.

The Hungarian writer, György Konrád, once wrote (2009):

Some time ago, a butcher lived in our village. He had a house on the corner of a steep street. There was a military base near the village. Once, the butcher’s wife was changing bedding and a tank crashed through the bedroom wall because the road was ice and slippery. The front of the house was damaged. The woman was also somewhat damaged, but not too much. When I met the butcher next time, I asked him about what happened. „History came to us,“ he said.

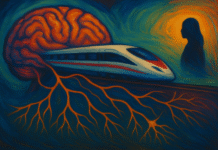

The grotesque presence of a tank in the bedroom describes the ever-repeating experience of losing a safe and familiar home, a very Central European experience of the unheimlich. People learned to live their „small histories“ in separation, avoiding the demonstration of their awkward existence when confronted with tanks. It encouraged the creation of hidden spaces, corridors, and labyrinths where no tanks could break into. When there were no such options available, the problem became one of getting used to tanks inside the bedrooms, pretending there were no tanks, or even including them in interior decoration of the bedrooms. People looked for various means such as perfecting the art of hiding and blending in with their surroundings. Of course, denial, idealization, and alienation are defense mechanisms often encountered in similar situations. Psychic retreats, a concept introduced by John Steiner, a Prague emigre, describes interpersonal spaces of relative safety and relief, paid for by isolation, withdrawal, and general stagnation. Sometimes such retreats are romanticized and admired, other times they have a rougher and perverse connotation.

The Czech intellectual, Pavel Kosatík expressed this in the following words (Kosatík, 2010):

„…they often found out that it is virtually impossible to get along and communicate with any new ruling power. It is possible to ignore it, to create one’s own world, indifferent to the real one, and hope that this parallel existence will provide enough meaning that will eventually weaken the power of the oppressor… The farther from the oppressor, the more freedom… To create a culture that is independent from the official one and that can persevere through any regime means to become self-sufficient and liberated from all.“

Psychoanalysis, similar to many other Central European intellectual movements, emerged in the midst of a constant struggle between external – and often violent – political forces and preservation of privacy. Although psychoanalysis has always focused on the „small” family context, constant external intrusions into these intimate settings affected psychoanalytic discourse.

It is not by accident that many of Freud’s examples are of eerie, strange and uncanny feelings related to the dissolution of intimate spaces, the loss of home, or to the bed, falling asleep and waking up. As we know, these “feelings are evoked when something that promises to be familiar, responsive or animate turns out to be unfamiliar, unresponsive or unanimate”. They are “the hallmark of a situation in which a person feels the lack of reciprocal dialogue or continuity … with another person who is permanently or momentarily fulfilling the (self-object) narcissistic function” (Bach, 1975). Freud’s essay „The Uncanny” (Freud, 2003) was published six years before Kafka’s novel „The Trial“(Kafka 2009) – a novel in which a great foreign power enters the bedroom of Josef K. Central European literature contains many similar traumatic examples – let’s mention Darkness at Noon by Arthur Koestler (2006), a novel set during the time of Stalinist purging trials. The external reality, represented by the government’s power, forcefully disrupts the process of dreaming in the individual, causing anxiety, anticipation of evil, and surreality. Of course, a patient dreaming on a couch and his analyst could feel threatened by tanks just as much as any other technology such as eavesdropping bugs or surveillance cameras. This made them incapable of distinguishing between what was real and what was a part of their fantasy or what is normal and what is perverse. To return to literature, let’s recall the leopards from Franz Kafka’s The Zürau Aphorisms (Kafka, 2006), who “break into the temple and drink all the sacrificial vessels dry – it keeps happening – in the end, it can be calculated in advance and is incorporated into the ritual.” In a similar way, there could be attempts in the analyst’s room to give Kafka’s imaginary leopards or Konrád´s tanks protective or fetishistic functions.

In a situation in which the patient feels a lack of dialogue and discontinuity with the analyst, narcissistic transference – counter-transference is repeatedly disrupted. The strange, uncanny anxiety is produced in the patient (or the analyst) when the other that gives promise of a dialogue is in fact discovered in fact not to offer this possibility. For instance, one candidate started his session by stating he was suggested by his employer to become a member of the Communist Party. His analyst, anxious about this information, lacked the necessary analytic function, psychic distance and time, and warned the patient that his training would be terminated should he join the Party. Such a reaction was so sudden and unexpected to the patient’s experience that he could not assimilate it. The analyst involved his own private life and the existence of illegal analytic practice, producing a traumatic effect in the analyst, which were then superimposed on the private life of the patient. To quote Janine Puget (Puget, 2002): “When analysts and patients are both simultaneously experiencing the same anxieties or preoccupations, arising from the context of their daily lives”, she speaks of superimposed worlds which cause a large scale of narcissistic relational disturbances of the analytic couple.

To provide some other examples, I will mention several moments from the practice of psychoanalysts in Communist Prague, in which the “tank in the bedroom” inevitably and sometimes strongly interfered with the natural course of their work and training of candidates. The majority of the analyses took place secretly – that is in hiding from a third party, unreliable colleagues, relatives, or secret services. The analysts were illegally charging for their sessions and the candidates were illegally paying for them, agreeing not to turn each other in. Therapy thus became an illegal good on the black market, something which no totalitarian regime managed to eliminate completely. The sessions and seminars took place in the domestic environment, sometimes in the analyst’s apartment, other times in the apartment of the candidate. Some candidates were aware of their analyst’s secret intentions to emigrate and even accompanied them to the airport. Other candidates knew that their analyst being followed by the secret police and that he could be arrested and investigated. One of the trainees was a close relative of the highest-ranking ideologists of the Communist Party. Another analyst, probably for career purposes, joined the Communist Party but continued to be involved in illegal activities. Another colleague distanced himself from psychoanalysis during the toughest times of Stalinism, turning in his coworkers, but then returned to psychoanalysis later and recruited many new supporters. Yet another Prague analyst, a Communist of Jewish descent, escaped to England from Hitler, only to return after the war to become the personal doctor of the first Communist president. Several years later, during the anti-Semitic trials of the fifties, he was arrested, tortured, and accused of hurting the president. He was facing death penalty, but while expecting the trial he maintained his Communist Party membership and secretly trained other future analysts. After the Second World War, his analyst, perhaps the only one who had managed to survive Hitler’s persecutions in Prague, was facing deportation to a gulag as a Russian emigre.

Only retroactively can we perceive these superimposed “tanks in the bedrooms” and their impact on the candidates and analysts, which then at the time could not have been sufficiently worked through. As Puget, studying psychoanalysis under the oppression in Argentine, points out in her excellent paper, the permanent movement from one world to another disrupts the process in which the analyst can listen to the patient. Inevitably, the analyst feels a growing desire to share, participate, or sympathize, which, however, leads to a secret, secondary, and eventually embarrassing affair and unconscious pacts with the patient. It is extremely difficult to preserve the boundary between “the field of analysis” and “the field of daily life” (Puget, 2002). Both participants are sometimes flooded by “the world of daily life, which has a high traumatic charge and violates the analytic situation”. The analytical material loses its mysterious nature which would normally inspire curiosity in the analyst and motivate him to decipher it. Everything is now understood literally and without secondary meanings. Both participants may enter a state governed by the sensory order, unable to carry out the analytic function. „The tank in the bedroom“ cannot be observed with analytic curiosity, and so disappears from analytic discourse and becomes invisible. The analyst and the patient become accomplices and mystifiers together in their transformation of therapy into a protective and mutually supportive blindness. As we know, these identifications which are stemming from the ego-ideal can also trigger off “heroic, deadly or perverse” (Puget, 2002) responses on the part of the candidate, the analyst, or both. Their perverted analytic cooperation could also cause strong ambivalent tensions and unresolved conflicts which would be then present even after the termination of the treatment in the post-analytic relationship. Sometimes, however, it succeeded at least partially to analyze various forms of former mutual mystification afterward. Furthermore, these tensions perhaps resulted in early terminations of training of some of the candidates. Also, some members have left the Society because they did not approve of its tense atmosphere and strong hierarchical structure.

Here you find third part of the article.

References

Bach, S. (1975). Narcissism, Continuity and the Uncanny. IJPA(56), pp. 77–86.

Freud, S. (2003). The Uncanny. Penguin Classics.

Kafka, F. (2006). The Zürau Aphorisms. Schocken.

Koestler, A. (2006). Darkness at Noon. Scribner.

Konrád, G. (2009). In J. Trávníček (Ed), V kleštích dějin: střední Evropa jako pojem a problém. Brno: Host.

Kosatík, P. (2010). České snění. Praha: Torst.

Puget, J. (2002). The State of Threat and Psychoanalysis: From the Uncanny that Structures to the Uncanny that Alienates. Free Associations: Psychoanalysis, Groups, Politics, Culture(9), pp. 611–648.